Opposition to United States involvement in the Vietnam War (before) or anti-Vietnam War movement (present) began with demonstrations in 1965 against the escalating

role of the United States in the Vietnam War

A role (also rôle or social role) is a set of connected behaviors, rights, obligations, beliefs, and norms as conceptualized by people in a social situation. It is an expected or free or continuously changing behavior and may have a given indivi ...

and grew into a broad

social movement

A social movement is a loosely organized effort by a large group of people to achieve a particular goal, typically a social or political one. This may be to carry out a social change, or to resist or undo one. It is a type of group action and may ...

over the ensuing several years. This movement informed and helped shape the vigorous and polarizing debate, primarily in the United States, during the second half of the 1960s and early 1970s on how to end the war.

Many in the

peace movement

A peace movement is a social movement which seeks to achieve ideals, such as the ending of a particular war (or wars) or minimizing inter-human violence in a particular place or situation. They are often linked to the goal of achieving world peac ...

within the United States were children, mothers, or

anti-establishment

An anti-establishment view or belief is one which stands in opposition to the conventional social, political, and economic principles of a society. The term was first used in the modern sense in 1958, by the British magazine ''New Statesman'' ...

youth. Opposition grew with participation by the African-American civil rights, second-wave feminist movements,

Chicano Movement

The Chicano Movement, also referred to as El Movimiento, was a social and political movement in the United States inspired by prior acts of resistance among people of Mexican descent, especially of Pachucos in the 1940s and 1950s, and the Black ...

s, and sectors of organized labor. Additional involvement came from many other groups, including educators, clergy, academics, journalists, lawyers, physicians such as

Benjamin Spock

Benjamin McLane Spock (May 2, 1903 – March 15, 1998) was an American pediatrician and left-wing political activist whose book '' Baby and Child Care'' (1946) is one of the best-selling books of the twentieth century, selling 500,000 copie ...

, and military

veteran

A veteran () is a person who has significant experience (and is usually adept and esteemed) and expertise in a particular occupation or field. A military veteran is a person who is no longer serving in a military.

A military veteran that has ...

s.

Their actions consisted mainly of peaceful,

nonviolent

Nonviolence is the personal practice of not causing harm to others under any condition. It may come from the belief that hurting people, animals and/or the environment is unnecessary to achieve an outcome and it may refer to a general philosoph ...

events; few events were deliberately provocative and violent. In some cases, police used violent tactics against peaceful demonstrators. By 1967, according to

Gallup poll

Gallup, Inc. is an American analytics and advisory company based in Washington, D.C. Founded by George Gallup in 1935, the company became known for its public opinion polls conducted worldwide. Starting in the 1980s, Gallup transitioned its bu ...

s, an increasing majority of Americans considered military involvement in Vietnam to be a mistake, echoed decades later by the then-head of American war planning, former Secretary of Defense

Robert McNamara

Robert Strange McNamara (; June 9, 1916 – July 6, 2009) was an American business executive and the eighth United States Secretary of Defense, serving from 1961 to 1968 under Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson. He remains the Lis ...

.

Background

Causes of opposition

The draft, a system of

conscription

Conscription (also called the draft in the United States) is the state-mandated enlistment of people in a national service, mainly a military service. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it continues in some countries to the present day un ...

that mainly drew from minorities and lower and middle class whites, drove much of the protest after 1965.

Conscientious objector

A conscientious objector (often shortened to conchie) is an "individual who has claimed the right to refuse to perform military service" on the grounds of freedom of thought, conscience, or religion. The term has also been extended to object ...

s played an active role despite their small numbers. The prevailing sentiment that the draft was unfairly administered fueled student and

blue-collar

A blue-collar worker is a working class person who performs manual labor. Blue-collar work may involve skilled or unskilled labor. The type of work may involving manufacturing, warehousing, mining, excavation, electricity generation and powe ...

American opposition to the military draft.

Opposition to the war arose during a time of unprecedented

student activism

Student activism or campus activism is work by students to cause political, environmental, economic, or social change. Although often focused on schools, curriculum, and educational funding, student groups have influenced greater political e ...

, which followed the

free speech movement

The Free Speech Movement (FSM) was a massive, long-lasting student protest which took place during the 1964–65 academic year on the campus of the University of California, Berkeley. The Movement was informally under the central leadership of B ...

and the

civil rights movement

The civil rights movement was a nonviolent social and political movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized institutional Racial segregation in the United States, racial segregation, Racial discrimination ...

. The military draft mobilized the

baby boomers

Baby boomers, often shortened to boomers, are the Western demographic cohort following the Silent Generation and preceding Generation X. The generation is often defined as people born from 1946 to 1964, during the mid-20th century baby boom. Th ...

, who were most at risk, but it grew to include a varied cross-section of Americans. The growing opposition to the Vietnam War was partly attributed to greater access to uncensored information through extensive television coverage on the ground in Vietnam.

Beyond opposition to the draft, anti-war protesters also made moral arguments against U.S. involvement in Vietnam. In May 1954, preceding the later Quaker protests but "just after the defeat of the French at

Dien Bien Phu, the

Service Committee bought a page in ''

The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' to protest what seemed to be the tendency of the USA to step into Indo-China as France stepped out. We expressed our fear that in so doing, America would back into a war."

The moral imperative argument against the war was especially popular among American college students, who were more likely than the general public to accuse the United States of having imperialistic goals in Vietnam and to criticize the war as "immoral." Civilian deaths, which were downplayed or omitted entirely by the Western media, became a subject of protest when photographic evidence of casualties emerged. An infamous photo of General

Nguyễn Ngọc Loan

Major General Nguyễn Ngọc Loan (; 11 December 193014 July 1998) was a South Vietnamese general and chief of the South Vietnamese National Police.

Loan gained international attention when he summarily executed handcuffed prisoner Nguyễn ...

shooting an alleged terrorist in handcuffs during the

Tet Offensive

The Tet Offensive was a major escalation and one of the largest military campaigns of the Vietnam War. It was launched on January 30, 1968 by forces of the Viet Cong (VC) and North Vietnamese People's Army of Vietnam (PAVN) against the forces o ...

also provoked public outcry.

[Guttmann, Allen. 1969. Protest against the War in Vietnam. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 382. pp. 56–63,]

Another element of the American opposition to the war was the perception that U.S. intervention in Vietnam, which had been argued as acceptable because of the

domino theory

The domino theory is a geopolitical theory which posits that increases or decreases in democracy in one country tend to spread to neighboring countries in a domino effect. It was prominent in the United States from the 1950s to the 1980s in the ...

and the threat of

communism

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a s ...

, was not legally justifiable. Some Americans believed that the communist threat was used as a scapegoat to hide imperialistic intentions, and others argued that the American intervention in South Vietnam interfered with the

self-determination

The right of a people to self-determination is a cardinal principle in modern international law (commonly regarded as a ''jus cogens'' rule), binding, as such, on the United Nations as authoritative interpretation of the Charter's norms. It stat ...

of the country and felt that the war in Vietnam was a civil war that ought to have determined the fate of the country and that America was wrong to intervene.

also shook the faith of citizens at home as new television brought images of wartime conflict to viewers at home. Newsmen like NBC's Frank McGee stated that the war was all but lost as a "conclusion to be drawn inescapably from the facts."

For the first time in American history, the media had the means to broadcast battlefield images. Graphic footage of casualties on the nightly news eliminated any myth of the glory of war. With no clear sign of victory in Vietnam, American military casualties helped stimulate opposition to the war by Americans. In their book ''

Manufacturing Consent

''Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media'' is a 1988 book by Edward S. Herman and Noam Chomsky. It argues that the mass communication media of the U.S. "are effective and powerful ideological institutions that carry out a ...

'',

Edward S. Herman

Edward Samuel Herman (April 7, 1925 – November 11, 2017) was an American economist, media scholar and social critic. Herman is known for his media criticism, in particular the propaganda model hypothesis he developed with Noam Chomsky, a fr ...

and

Noam Chomsky

Avram Noam Chomsky (born December 7, 1928) is an American public intellectual: a linguist, philosopher, cognitive scientist, historian, social critic, and political activist. Sometimes called "the father of modern linguistics", Chomsky is ...

reject the mainstream view of how the media influenced the war and propose that the media instead censored the more brutal images of the fighting and the death of millions of innocent people.

Polarization

The U.S. became polarized over the war. Many supporters of U.S. involvement argued for what was known as the

domino theory

The domino theory is a geopolitical theory which posits that increases or decreases in democracy in one country tend to spread to neighboring countries in a domino effect. It was prominent in the United States from the 1950s to the 1980s in the ...

, a theory that believed if one country fell to communism, then the bordering countries would be sure to fall as well, much like falling dominoes. This theory was largely held due to the fall of eastern Europe to communism and the Soviet sphere of influence following World War II. However, military critics of the war pointed out that the Vietnam War was political and that the military mission lacked any clear idea of how to achieve its objectives. Civilian critics of the war argued that the government of South Vietnam lacked political legitimacy, or that support for the war was completely immoral.

The media also played a substantial role in the polarization of American opinion regarding the Vietnam War. For example, in 1965 a majority of the media attention focused on military tactics with very little discussion about the necessity for a full scale intervention in Southeast Asia.

[Herman, Edward S. & Chomsky, Noam. (2002) Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media. New York: Pantheon Books.] After 1965, the media covered the dissent and domestic controversy that existed within the United States, but mostly excluded the actual view of dissidents and resisters.

The media established a sphere of public discourse surrounding the Hawk versus Dove debate. The Dove was a liberal and a critic of the war. Doves claimed that the war was well–intentioned but a disastrously wrong mistake in an otherwise benign foreign policy. It is important to note the Doves did not question the U.S. intentions in intervening in Vietnam, nor did they question the morality or legality of the U.S. intervention. Rather, they made pragmatic claims that the war was a mistake. Contrarily, the Hawks argued that the war was legitimate and winnable and a part of the benign U.S. foreign policy. The Hawks claimed that the one-sided criticism of the media contributed to the decline of public support for the war and ultimately helped the U.S. lose the war. Author William F. Buckley repeatedly wrote about his approval for the war and suggested that "The United States has been timid, if not cowardly, in refusing to seek 'victory' in Vietnam."

The hawks claimed that the liberal media was responsible for the growing popular disenchantment with the war and blamed the western media for losing the war in Southeast Asia as communism was no longer a threat for them.

History

Early protests

Early organized opposition was led by American

Quaker

Quakers are people who belong to a historically Protestant Christian set of Christian denomination, denominations known formally as the Religious Society of Friends. Members of these movements ("theFriends") are generally united by a belie ...

s in the 1950s, and by November 1960 eleven hundred Quakers undertook a silent protest vigil -- the group "ringed the Pentagon for parts of two days".

[

Protests bringing attention to "]the draft

Conscription (also called the draft in the United States) is the state-mandated enlistment of people in a national service, mainly a military service. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it continues in some countries to the present day un ...

" began on May 5, 1965. Student activists at the University of California, Berkeley marched on the Berkeley Draft board

{{further, Conscription in the United StatesDraft boards are a part of the Selective Service System which register and select men of military age in the event of conscription in the United States.

Local board

The local draft board is a board th ...

and forty students staged the first public burning of a draft card in the United States. Another nineteen cards were burnt on May 22 at a demonstration following the Berkeley teach-in

A teach-in is similar to a general educational forum on any complicated issue, usually an issue involving current political affairs. The main difference between a teach-in and a seminar is the refusal to limit the discussion to a specific time fr ...

. Draft card protests were not aimed so much at the draft as at the immoral conduct of the war.

At that time, only a fraction of all men of draft age were actually conscripted

Conscription (also called the draft in the United States) is the state-mandated enlistment of people in a national service, mainly a military service. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it continues in some countries to the present day un ...

, but the Selective Service System

The Selective Service System (SSS) is an Independent agencies of the United States government, independent agency of the Federal government of the United States, United States government that maintains information on U.S. Citizenship of the Unite ...

office ("Draft Board") in each locality had broad discretion on whom to draft and whom to exempt where there was no clear guideline for exemption. In late July 1965, Johnson doubled the number of young men to be drafted per month from 17,000 to 35,000, and on August 31, signed a law making it a crime to burn a draft card.

On October 15, 1965, the student-run National Coordinating Committee to End the War in Vietnam in New York staged the first draft card burning to result in an arrest under the new law.

Gruesome images of two anti-war activists who set themselves on fire in November 1965 provided iconic images of how strongly some people felt that the war was immoral. On November 2, 32-year-old Quaker

Quakers are people who belong to a historically Protestant Christian set of Christian denomination, denominations known formally as the Religious Society of Friends. Members of these movements ("theFriends") are generally united by a belie ...

Norman Morrison

Norman R. Morrison (December 29, 1933 – November 2, 1965) was an American anti-war activist best known for his act of self-immolation at age 31 to protest United States involvement in the Vietnam War. On November 2, 1965, Morrison doused himse ...

set himself on fire in front of The Pentagon

The Pentagon is the headquarters building of the United States Department of Defense. It was constructed on an accelerated schedule during World War II. As a symbol of the U.S. military, the phrase ''The Pentagon'' is often used as a metony ...

. On November 9, 22-year-old Catholic Worker Movement

The Catholic Worker Movement is a collection of autonomous communities of Catholics and their associates founded by Dorothy Day and Peter Maurin in the United States in 1933. Its aim is to "live in accordance with the justice and charity of Jesus ...

member Roger Allen LaPorte did the same in front of United Nations Headquarters

The United Nations is headquartered in Midtown Manhattan, New York City, United States, and the complex has served as the official headquarters of the United Nations since its completion in 1951. It is in the Turtle Bay, Manhattan, Turtle Bay neig ...

in New York City. Both protests were conscious imitations of earlier (and ongoing) Buddhist protests in South Vietnam.

Government reactions

The growing anti-war movement alarmed many in the U.S. government. On August 16, 1966, the House Un-American Activities Committee

The House Committee on Un-American Activities (HCUA), popularly dubbed the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), was an investigative committee of the United States House of Representatives, created in 1938 to investigate alleged disloy ...

(HUAC) began investigations of Americans who were suspected of aiding the NLF, with the intent to introduce legislation making these activities illegal. Anti-war demonstrators disrupted the meeting and 50 were arrested.

Shifting opinion

In February 1967, ''

In February 1967, ''The New York Review of Books

''The New York Review of Books'' (or ''NYREV'' or ''NYRB'') is a semi-monthly magazine with articles on literature, culture, economics, science and current affairs. Published in New York City, it is inspired by the idea that the discussion of i ...

'' published " The Responsibility of Intellectuals", an essay by Noam Chomsky

Avram Noam Chomsky (born December 7, 1928) is an American public intellectual: a linguist, philosopher, cognitive scientist, historian, social critic, and political activist. Sometimes called "the father of modern linguistics", Chomsky is ...

, one of the leading intellectual opponents of the war. In the essay Chomsky argued that much responsibility for the war lay with liberal intellectuals and technical experts who were providing what he saw as pseudoscientific

Pseudoscience consists of statements, beliefs, or practices that claim to be both scientific and factual but are incompatible with the scientific method. Pseudoscience is often characterized by contradictory, exaggerated or unfalsifiable claim ...

justification for the policies of the U.S. government. The Time Inc magazines ''Time'' and ''Life'' maintained a very pro-war editorial stance until October 1967, when in a ''volte-face'', the editor-in-chief, Hedley Donovan

Hedley Donovan (May 24, 1914 – August 13, 1990) was editor in chief of Time Inc. from 1964 to 1979. In this capacity, he oversaw all of the company's magazine publications, including ''Time'', ''Life'', ''Fortune'', ''Sports Illustrated'', ''Mo ...

, came out against the war. Donovan wrote in an editorial in ''Life'' that the United States had gone into Vietnam for "honorable and sensible purposes", but the war had turned out to be "harder, longer, more complicated" than expected.[Karnow, Stanley ''Vietnam'' p. 489.] Donovan ended his editorial by writing the war was "not worth winning", as South Vietnam was "not absolutely imperative" to maintain American interests in Asia, which made it impossible "to ask young Americans to die for".

Draft protests

In 1967, the continued operation of a seemingly unfair draft system then calling as many as 40,000 men for induction each month fueled a burgeoning draft resistance movement. The draft favored white, middle-class men, which allowed an economically and racially discriminating draft to force young African American men to serve in rates that were disproportionately higher than the general population. Although in 1967 there was a smaller field of draft-eligible black men, 29 percent, versus 63 percent of white men, 64 percent of eligible black men were chosen to serve in the war through conscription, compared to only 31 percent of eligible white men.

On October 16, 1967, draft card turn-ins were held across the country, yielding more than 1,000 draft cards, later returned to the Justice Department

A justice ministry, ministry of justice, or department of justice is a ministry or other government agency in charge of the administration of justice. The ministry or department is often headed by a minister of justice (minister for justice in a ...

as an act of civil disobedience

Civil disobedience is the active, professed refusal of a citizen to obey certain laws, demands, orders or commands of a government (or any other authority). By some definitions, civil disobedience has to be nonviolent to be called "civil". Hen ...

. Resisters expected to be prosecuted immediately, but Attorney General

In most common law jurisdictions, the attorney general or attorney-general (sometimes abbreviated AG or Atty.-Gen) is the main legal advisor to the government. The plural is attorneys general.

In some jurisdictions, attorneys general also have exec ...

Ramsey Clark

William Ramsey Clark (December 18, 1927 – April 9, 2021) was an American lawyer, activist, and federal government official. A progressive, New Frontier liberal, he occupied senior positions in the United States Department of Justice under Presi ...

instead prosecuted a group of ringleaders including Dr. Benjamin Spock

Benjamin McLane Spock (May 2, 1903 – March 15, 1998) was an American pediatrician and left-wing political activist whose book '' Baby and Child Care'' (1946) is one of the best-selling books of the twentieth century, selling 500,000 copie ...

and Yale chaplain William Sloane Coffin, Jr. in Boston in 1968. By the late 1960s, one quarter of all court cases dealt with the draft, including men accused of draft-dodging and men petitioning for the status of conscientious objector

A conscientious objector (often shortened to conchie) is an "individual who has claimed the right to refuse to perform military service" on the grounds of freedom of thought, conscience, or religion. The term has also been extended to object ...

. Over 210,000 men were accused of draft-related offenses, 25,000 of whom were indicted.

Developments in the war

On February 1, 1968, Nguyễn Văn Lém

Nguyễn () is the most common Vietnamese surname. Outside of Vietnam, the surname is commonly rendered without diacritics as Nguyen. Nguyên (元)is a different word and surname.

By some estimates 39 percent of Vietnamese people bear this s ...

, a Vietcong

,

, war = the Vietnam War

, image = FNL Flag.svg

, caption = The flag of the Viet Cong, adopted in 1960, is a variation on the flag of North Vietnam. Sometimes the lower stripe was green.

, active ...

officer suspected of participating in murder of South Vietnamese government officials during the Tet Offensive

The Tet Offensive was a major escalation and one of the largest military campaigns of the Vietnam War. It was launched on January 30, 1968 by forces of the Viet Cong (VC) and North Vietnamese People's Army of Vietnam (PAVN) against the forces o ...

, was summarily executed

A summary execution is an execution in which a person is accused of a crime and immediately killed without the benefit of a full and fair trial. Executions as the result of summary justice (such as a drumhead court-martial) are sometimes include ...

by General Nguyễn Ngọc Loan

Major General Nguyễn Ngọc Loan (; 11 December 193014 July 1998) was a South Vietnamese general and chief of the South Vietnamese National Police.

Loan gained international attention when he summarily executed handcuffed prisoner Nguyễn ...

, the South Vietnamese National Police Chief. Loan shot Lém in the head on a public street in Saigon

, population_density_km2 = 4,292

, population_density_metro_km2 = 697.2

, population_demonym = Saigonese

, blank_name = GRP (Nominal)

, blank_info = 2019

, blank1_name = – Total

, blank1_ ...

, despite being in front of journalists. South Vietnamese reports provided as justification after the fact claimed that Lém was captured near the site of a ditch holding as many as thirty-four bound and shot bodies of police and their relatives, some of whom were the families of General Loan's deputy and close friend. The execution provided an iconic image that helped sway public opinion in the United States against the war.

The events of Tet in early 1968 as a whole were also remarkable in shifting public opinion regarding the war. U.S. military officials had previously reported that counter-insurgency in South Vietnam was being prosecuted successfully. While the Tet Offensive provided the U.S. and allied militaries with a great victory in that the Vietcong was finally brought into open battle and destroyed as a fighting force, the American media, including respected figures such as Walter Cronkite

Walter Leland Cronkite Jr. (November 4, 1916 – July 17, 2009) was an American broadcast journalist who served as anchorman for the ''CBS Evening News'' for 19 years (1962–1981). During the 1960s and 1970s, he was often cited as "the mo ...

, interpreted such events as the attack on the American embassy in Saigon as an indicator of U.S. military weakness. The military victories on the battlefields of Tet were obscured by shocking images of violence on television screens, long casualty lists, and a new perception among the American people that the military had been untruthful to them about the success of earlier military operations, and ultimately, the ability to achieve a meaningful military solution in Vietnam.

1968 presidential election

In 1968, President Lyndon B. Johnson began his re-election campaign. Eugene McCarthy

Eugene Joseph McCarthy (March 29, 1916December 10, 2005) was an American politician, writer, and academic from Minnesota. He served in the United States House of Representatives from 1949 to 1959 and the United States Senate from 1959 to 1971. ...

ran against him for the nomination on an anti-war platform. McCarthy did not win the first primary election in New Hampshire

New Hampshire is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the northeastern United States. It is bordered by Massachusetts to the south, Vermont to the west, Maine and the Gulf of Maine to the east, and the Canadian province of Quebec t ...

, but he did surprisingly well against an incumbent. The resulting blow to the Johnson campaign, taken together with other factors, led the President to make a surprise announcement in a March 31 televised speech that he was pulling out of the race. He also announced the initiation of the Paris Peace Negotiations with Vietnam in that speech. Then, on August 4, 1969, U.S. representative Henry Kissinger

Henry Alfred Kissinger (; ; born Heinz Alfred Kissinger, May 27, 1923) is a German-born American politician, diplomat, and geopolitical consultant who served as United States Secretary of State and National Security Advisor under the presid ...

and North Vietnamese representative Xuan Thuy

Xuan () may refer to:

* Xuancheng, formerly Xuan Prefecture (Xuanzhou), Anhui, China

** Xuanzhou District, seat of Xuancheng and Xuan Prefecture

** Xuan paper, from Xuan Prefecture

* Xuan (surname), Chinese surname

* Xuan (given name)

Chinese r ...

began secret peace negotiations at the apartment of French intermediary Jean Sainteny

Jean Sainteny or Jean Roger (29 May 1907, in Vésinet – 25 February 1978) was a French politician who was sent to Vietnam after the end of the Second World War in order to accept the surrender of the Japanese forces and to attempt to re-annex V ...

in Paris.

After breaking with Johnson's pro-war stance, Robert F. Kennedy

Robert Francis Kennedy (November 20, 1925June 6, 1968), also known by his initials RFK and by the nickname Bobby, was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 64th United States Attorney General from January 1961 to September 1964, ...

entered the race on March 16 and ran for the nomination on an anti-war platform. Johnson's vice president, Hubert Humphrey

Hubert Horatio Humphrey Jr. (May 27, 1911 – January 13, 1978) was an American pharmacist and politician who served as the 38th vice president of the United States from 1965 to 1969. He twice served in the United States Senate, representing Mi ...

, also ran for the nomination, promising to continue to support the South Vietnamese government.

Moratorium to End the War in Vietnam

In May 1969, ''Life'' magazine published in a single issue photographs of the faces of the roughly 250 or so American servicemen who had been killed in Vietnam during a "routine week" of war in the spring of 1969.truancy

Truancy is any intentional, unjustified, unauthorised, or illegal absence from compulsory education. It is a deliberate absence by a student's own free will (though sometimes adults or parents will allow and/or ignore it) and usually does not refe ...

from school. About 15 million Americans took part in the demonstration of October 15, making it the largest protests in a single day up to that point. A second round of "Moratorium" demonstrations was held on November 15 and attracted more people than the first.

Hearts and Minds campaign

The U.S. realized that the South Vietnamese government needed a solid base of popular support if it were to survive the insurgency. To pursue this goal of winning the " Hearts and Minds" of the Vietnamese people, units of the

The U.S. realized that the South Vietnamese government needed a solid base of popular support if it were to survive the insurgency. To pursue this goal of winning the " Hearts and Minds" of the Vietnamese people, units of the United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cla ...

, referred to as " Civil Affairs" units, were used extensively for the first time since World War II.

Civil Affairs units, while remaining armed and under direct military control, engaged in what came to be known as "nation-building

Nation-building is constructing or structuring a national identity using the power of the state. Nation-building aims at the unification of the people within the state so that it remains politically stable and viable in the long run. According to ...

": constructing (or reconstructing) schools, public buildings, roads and other infrastructure

Infrastructure is the set of facilities and systems that serve a country, city, or other area, and encompasses the services and facilities necessary for its economy, households and firms to function. Infrastructure is composed of public and priv ...

; conducting medical programs for civilians who had no access to medical facilities; facilitating cooperation among local civilian leaders; conducting hygiene and other training for civilians; and similar activities.

This policy of attempting to win the hearts and minds of the Vietnamese people, however, often was at odds with other aspects of the war which sometimes served to antagonize many Vietnamese civilians and provided ammunition to the anti-war movement. These included the emphasis on "body count

A body count is the total number of people killed in a particular event. In combat, a body count is often based on the number of confirmed kills, but occasionally only an estimate. Often used in reference to military combat, the term can also r ...

" as a way of measuring military success on the battlefield, civilian casualties during the bombing of villages (symbolized by journalist Peter Arnett

Peter Gregg Arnett (born 13 November 1934) is a New Zealand-born American journalist. He is known for his coverage of the Vietnam War and the Gulf War. He was awarded the 1966 Pulitzer Prize in International Reporting for his work in Vietn ...

's famous quote, "it was necessary to destroy the village to save it"), and the killing of civilians in such incidents as the My Lai massacre

My or MY may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* My (radio station), a Malaysian radio station

* Little My, a fictional character in the Moomins universe

* ''My'' (album), by Edyta Górniak

* ''My'' (EP), by Cho Mi-yeon

Business

* Market ...

. In 1974 the documentary ''Hearts and Minds'' sought to portray the devastation the war was causing to the South Vietnamese people, and won an Academy Award

The Academy Awards, better known as the Oscars, are awards for artistic and technical merit for the American and international film industry. The awards are regarded by many as the most prestigious, significant awards in the entertainment ind ...

for best documentary amid considerable controversy. The South Vietnamese government also antagonized many of its citizens with its suppression of political opposition, through such measures as holding large numbers of political prisoners, torturing political opponents, and holding a one-man election for President in 1971. Covert counter-terror programs and semi-covert ones such as the Phoenix Program

The Phoenix Program ( vi, Chiến dịch Phụng Hoàng) was designed and initially coordinated by the United States Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) during the Vietnam War, involving the American, Australian, and South Vietnamese militaries ...

attempted, with the help of anthropologists, to isolate rural South Vietnamese villages and affect the loyalty of the residents.

Increasing polarization

Despite the increasingly depressing news of the war, many Americans continued to support President Johnson's endeavors. Aside from the domino theory mentioned above, there was a feeling that the goal of preventing a communist takeover of a pro-Western government in South Vietnam was a noble objective. Many Americans were also concerned about saving face in the event of disengaging from the war or, as President Richard M. Nixon later put it, "achieving Peace with Honor." In addition, instances of Viet Cong atrocities were widely reported, most notably in an article that appeared in ''

Despite the increasingly depressing news of the war, many Americans continued to support President Johnson's endeavors. Aside from the domino theory mentioned above, there was a feeling that the goal of preventing a communist takeover of a pro-Western government in South Vietnam was a noble objective. Many Americans were also concerned about saving face in the event of disengaging from the war or, as President Richard M. Nixon later put it, "achieving Peace with Honor." In addition, instances of Viet Cong atrocities were widely reported, most notably in an article that appeared in ''Reader's Digest

''Reader's Digest'' is an American general-interest family magazine, published ten times a year. Formerly based in Chappaqua, New York, it is now headquartered in midtown Manhattan. The magazine was founded in 1922 by DeWitt Wallace and his wi ...

'' in 1968 entitled ''The Blood-Red Hands of Ho Chi Minh''.

However, anti-war feelings also began to rise. Many Americans opposed the war on moral grounds, appalled by the devastation and violence of the war. Others claimed the conflict was a war against Vietnamese independence, or an intervention in a foreign civil war

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

; others opposed it because they felt it lacked clear objectives and appeared to be unwinnable. Many anti-war activists were themselves Vietnam veteran

A Vietnam veteran is a person who served in the armed forces of participating countries during the Vietnam War.

The term has been used to describe veterans who served in the armed forces of South Vietnam, the United States Armed Forces, and oth ...

s, as evidenced by the organization Vietnam Veterans Against the War

Vietnam Veterans Against the War (VVAW) is an American tax-exempt non-profit organization and corporation founded in 1967 to oppose the United States policy and participation in the Vietnam War. VVAW says it is a national veterans' organization ...

.

Later protests

In April 1971, thousands of these veterans converged on the White House in Washington, D.C., and hundreds of them threw their medal

A medal or medallion is a small portable artistic object, a thin disc, normally of metal, carrying a design, usually on both sides. They typically have a commemorative purpose of some kind, and many are presented as awards. They may be int ...

s and decorations

Decoration may refer to:

* Decorative arts

* A house painter and decorator's craft

* An act or object intended to increase the beauty of a person, room, etc.

* An award that is a token of recognition to the recipient intended for wearing

Other ...

on the steps of the United States Capitol

The United States Capitol, often called The Capitol or the Capitol Building, is the seat of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, which is formally known as the United States Congress. It is located on Capitol Hill ...

. By this time, it had also become commonplace for the most radical anti-war demonstrators to prominently display the flag of the Viet Cong "enemy", an act which alienated many who were otherwise morally opposed to the war.

Characteristics

As the Vietnam War continued to escalate, public disenchantment grew and a variety of different groups were formed or became involved in the movement.

African Americans

African-American leaders of earlier decades like W. E. B. Du Bois were often

African-American leaders of earlier decades like W. E. B. Du Bois were often anti-imperialist

Anti-imperialism in political science and international relations is a term used in a variety of contexts, usually by nationalist movements who want to secede from a larger polity (usually in the form of an empire, but also in a multi-ethnic so ...

and anti-capitalist. Paul Robeson

Paul Leroy Robeson ( ; April 9, 1898 – January 23, 1976) was an American bass-baritone concert artist, stage and film actor, professional football player, and activist who became famous both for his cultural accomplishments and for his p ...

weighed in on the Vietnamese struggle in 1954, calling Ho Chi Minh

(: ; born ; 19 May 1890 – 2 September 1969), commonly known as ('Uncle Hồ'), also known as ('President Hồ'), (' Old father of the people') and by other aliases, was a Vietnamese revolutionary and statesman. He served as Prime ...

"the modern day Toussaint L'Overture, leading his people to freedom." These figures were driven from public life by McCarthyism, however, and black leaders were more cautious about criticizing US foreign policy as the 1960s began.

By the middle of the decade, open condemnation of the war became more common, with figures like Malcolm X

Malcolm X (born Malcolm Little, later Malik el-Shabazz; May 19, 1925 – February 21, 1965) was an American Muslim minister and human rights activist who was a prominent figure during the civil rights movement. A spokesman for the Nation of Is ...

and Bob Moses Robert Moses (1888–1981) was an American city planner.

Robert Moses may also refer to:

* Bob Moses (activist) (1935–2021), American educator and civil rights activist

* Bob Moses, American football player in the 1962 Cotton Bowl Classic

* Bob M ...

speaking out. Champion boxer Muhammad Ali

Muhammad Ali (; born Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr.; January 17, 1942 – June 3, 2016) was an American professional boxer and activist. Nicknamed "The Greatest", he is regarded as one of the most significant sports figures of the 20th century, a ...

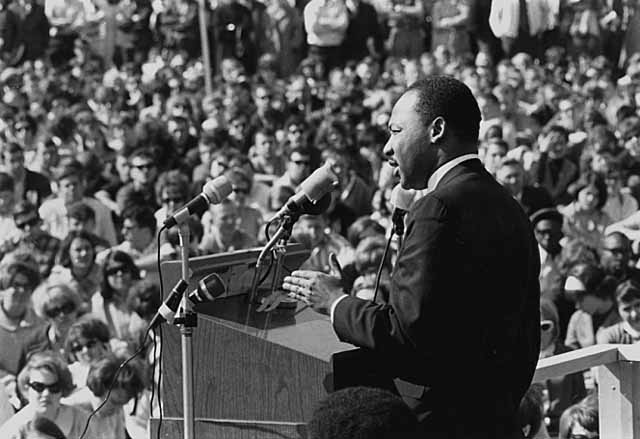

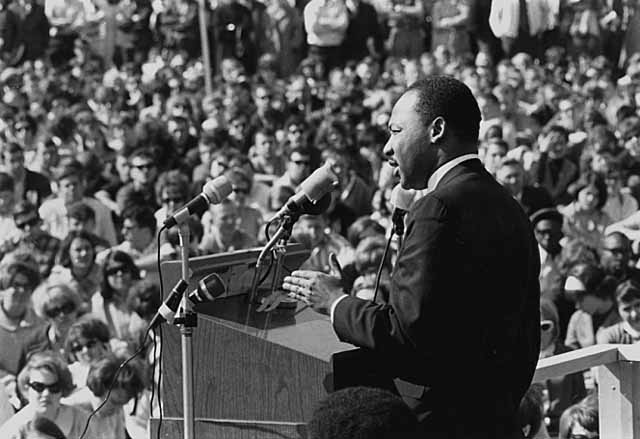

risked his career and a prison sentence to resist the draft in 1966. Soon Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr. (born Michael King Jr.; January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968) was an American Baptist minister and activist, one of the most prominent leaders in the civil rights movement from 1955 until his assassination in 1968 ...

, Coretta Scott King

Coretta Scott King ( Scott; April 27, 1927 – January 30, 2006) was an American author, activist, and civil rights leader who was married to Martin Luther King Jr. from 1953 until his death. As an advocate for African-American equality, she w ...

and James Bevel

James Luther Bevel (October 19, 1936 – December 19, 2008) was a minister and leader of the 1960s Civil Rights Movement in the United States. As a member of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), and then as its Director of Direct ...

of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) became prominent opponents of the Vietnam War, and Bevel became the director of the National Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam

The Spring Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam, which became the National Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam, was a coalition of American antiwar activists formed in November 1966 to organize large demonstrations in o ...

. The Black Panther Party

The Black Panther Party (BPP), originally the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense, was a Marxist-Leninist and black power political organization founded by college students Bobby Seale and Huey P. Newton in October 1966 in Oakland, Califo ...

vehemently opposed U.S. involvement in Vietnam.Selma march

The Selma to Montgomery marches were three protest marches, held in 1965, along the 54-mile (87 km) highway from Selma, Alabama, to the state capital of Montgomery. The marches were organized by nonviolent activists to demonstrate the ...

when he told a journalist that "millions of dollars can be spent every day to hold troops in South Vietnam and our country cannot protect the rights of Negroes in Selma".Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC, often pronounced ) was the principal channel of student commitment in the United States to the civil rights movement during the 1960s. Emerging in 1960 from the student-led sit-ins at segrega ...

(SNCC) became the first major civil rights group to issue a formal statement against the war. When SNCC-backed Georgia Representative Julian Bond

Horace Julian Bond (January 14, 1940 – August 15, 2015) was an American social activist, leader of the civil rights movement, politician, professor, and writer. While he was a student at Morehouse College in Atlanta, Georgia, during the e ...

acknowledged his agreement with the anti-war statement, he was refused his seat by the State of Georgia, an injustice which he successfully appealed up to the Supreme Court. SNCC had special significance as a nexus between the student movement and the black movement. At an SDS-organized conference at UC Berkeley

The University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley, Berkeley, Cal, or California) is a public university, public land-grant university, land-grant research university in Berkeley, California. Established in 1868 as the University of Californi ...

in October 1966, SNCC Chair Stokely Carmichael

Kwame Ture (; born Stokely Standiford Churchill Carmichael; June 29, 1941November 15, 1998) was a prominent organizer in the civil rights movement in the United States and the global pan-African movement. Born in Trinidad, he grew up in the Unite ...

challenged the white left to escalate their resistance to the military draft in a manner similar to the black movement. Some participants in ghetto rebellions of the era had already associated their actions with opposition to the Vietnam War, and SNCC first disrupted an Atlanta draft board in August 1966. According to historians Joshua Bloom and Waldo Martin, SDS's first Stop the Draft Week of October 1967 was "inspired by Black Power ndemboldened by the ghetto rebellions." SNCC appear to have originated the popular anti-draft slogan: "Hell no! We won't go!"

On April 4, 1967, King gave a much publicized speech entitled " Beyond Vietnam: A Time to Break Silence" at the Riverside Church in New York, attacking President Johnson for "deadly Western arrogance", declaring that "we are on the side of the wealthy, and the secure, while we create a hell for the poor".Ralph Bunche

Ralph Johnson Bunche (; August 7, 1904 – December 9, 1971) was an American political scientist, diplomat, and leading actor in the mid-20th-century decolonization process and US civil rights movement, who received the 1950 Nobel Peace Prize f ...

who argued that it was folly to associate the civil rights movement with the anti-Vietnam war movement, maintaining that this would set back civil rights for African Americans.

Artists

Many artists during the 1960s and 1970s opposed the war and used their creativity and careers to visibly oppose the war. Writers and poets opposed to involvement in the war included Allen Ginsberg

Irwin Allen Ginsberg (; June 3, 1926 – April 5, 1997) was an American poet and writer. As a student at Columbia University in the 1940s, he began friendships with William S. Burroughs and Jack Kerouac, forming the core of the Beat Gener ...

, Denise Levertov

Priscilla Denise Levertov (24 October 1923 – 20 December 1997) was a British-born naturalised American poet. She was a recipient of the Lannan Literary Award for Poetry.

Early life and influences

Levertov was born and grew up in Ilford, Ess ...

, Robert Duncan, and Robert Bly

Robert Elwood Bly (December 23, 1926 – November 21, 2021) was an American poet, essayist, activist and leader of the mythopoetic men's movement. His best-known prose book is '' Iron John: A Book About Men'' (1990), which spent 62 weeks on ' ...

. Their pieces often incorporated imagery based on the tragic events of the war as well as the disparity between life in Vietnam and life in the United States. Visual artists Ronald Haeberle, Peter Saul

Peter Saul (born August 16, 1934) is an American painter. His work has connections with Pop Art, Surrealism, and Expressionism. His early use of pop culture cartoon references in the late 1950s and very early 1960s situates him as one of the fa ...

, and Nancy Spero

Nancy Spero (August 24, 1926 – October 18, 2009) was an American visual artist. Born in Cleveland, Ohio, Spero lived for much of her life in New York City. She married and collaborated with artist Leon Golub. As both artist and activist, Nanc ...

, among others, used war equipment, like guns and helicopters, in their works while incorporating important political and war figures, portraying to the nation exactly who was responsible for the violence. Filmmakers such as Lenny Lipton

Leonard Lipton (May 18, 1940 – October 5, 2022) was an American author, filmmaker, lyricist and inventor. At age 19, Lipton wrote the poem that became the basis for the lyrics to the song "Puff, the Magic Dragon". He went on to write books on ...

, Jerry Abrams, Peter Gessner, and David Ringo created documentary-style movies featuring actual footage from the antiwar marches to raise awareness about the war and the diverse opposition movement. Playwrights like Frank O'Hara

Francis Russell "Frank" O'Hara (March 27, 1926 – July 25, 1966) was an American writer, poet, and art critic. A curator at the Museum of Modern Art, O'Hara became prominent in New York City's art world. O'Hara is regarded as a leading figure i ...

, Sam Shepard

Samuel Shepard Rogers III (November 5, 1943 – July 27, 2017) was an American actor, playwright, author, screenwriter, and director whose career spanned half a century. He won 10 Obie Awards for writing and directing, the most by any write ...

, Robert Lowell

Robert Traill Spence Lowell IV (; March 1, 1917 – September 12, 1977) was an American poet. He was born into a Boston Brahmin family that could trace its origins back to the ''Mayflower''. His family, past and present, were important subjects i ...

, Megan Terry

Megan Terry (born July 22, 1932) is an American playwright, screenwriter, and theatre artist.

She has produced over fifty works for theater, radio, and television, and is best known for her avant-garde theatrical work from the 1960s. As a found ...

, Grant Duay, and Kenneth Bernard

Kenneth Otis Bernard (May 7, 1930 – August 9, 2020) was an American author, poet, and playwright.

Bernard was born in Brooklyn and raised in Framingham, Massachusetts; he lived his adult life in New York City. He married Elaine Ceil Reiss ...

used theater as a vehicle for portraying their thoughts about the Vietnam War, often satirizing the role of America in the world and juxtaposing the horrific effects of war with normal scenes of life. Regardless of medium, antiwar artists ranged from pacifists to violent radicals and caused Americans to think more critically about the war. Art as war opposition was quite popular in the early years of the war, but soon faded as political activism became the more common and most visible way of opposing the war.

Asian-Americans

Many Asian-Americans were strongly opposed to the Vietnam War. They saw the war as being a bigger action of U.S. imperialism and "connected the oppression of the Asians in the United States to the prosecution of the war in Vietnam."teach-in

A teach-in is similar to a general educational forum on any complicated issue, usually an issue involving current political affairs. The main difference between a teach-in and a seminar is the refusal to limit the discussion to a specific time fr ...

s and demonstrations. During marches, Asian American activists carried banners that read "Stop the Bombing of Asian People and Stop Killing Our Asian Brothers and Sisters." Its newsletter stated, "our goal is to build a solid, broad-based anti-imperialist movement of Asian people against the war in Vietnam."

The anti-war sentiment by Asian Americans was fueled by the racial inequality

Social inequality occurs when resources in a given society are distributed unevenly, typically through norms of allocation, that engender specific patterns along lines of socially defined categories of persons. It posses and creates gender c ...

that they faced in the United States. As historian Daryl Maeda notes, "the antiwar movement articulated Asian Americans' racial commonality with Vietnamese people in two distinctly gendered ways: identification based on the experiences of male soldiers and identification by women." Asian American soldiers in the U.S. military were many times classified as being like the enemy. They were referred to as gook

Gook ( or ) is a derogatory term for people of East and Southeast Asian descent. Its origin is unclear, but it may have originated among U.S. Marines during the Philippine–American War (1899–1902) and Korean War. Historically, U.S. military p ...

s and had a racialized identity in comparison to their non-Asian counterparts. There was also the hypersexualization of Vietnamese women which in turn affected how Asian American women in the military were treated. "In a Gidra article, prominent influential newspaper of the Asian American movement Evelyn Yoshimura noted that the U.S. military systematically portrayed Vietnamese women as prostitutes

Prostitution is the business or practice of engaging in sexual activity in exchange for payment. The definition of "sexual activity" varies, and is often defined as an activity requiring physical contact (e.g., sexual intercourse, non-penet ...

as a way of dehumanizing them." Asian American groups realized in order to extinguish racism

Racism is the belief that groups of humans possess different behavioral traits corresponding to inherited attributes and can be divided based on the superiority of one race over another. It may also mean prejudice, discrimination, or antagonism ...

, they also had to address sexism as well. This in turn led to women's leadership in the Asian American antiwar movement. Patsy Chan, a "Third World" activist, said at an antiwar rally in San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish language, Spanish for "Francis of Assisi, Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the List of Ca ...

, "We, as Third World

The term "Third World" arose during the Cold War to define countries that remained non-aligned with either NATO or the Warsaw Pact. The United States, Canada, Japan, South Korea, Western European nations and their allies represented the " First ...

women xpress Xpress may refer to:

*Xpress (TV series), an award-winning multi cultural entertainment series

*Xpress, a regional passenger bus service provided by the Georgia Regional Transportation Authority in metropolitan Atlanta

* X*Press X*Change, an obsol ...

our militant solidarity with our brothers and sisters from Indochina. We, as Third World people know of the struggle the Indochinese

Mainland Southeast Asia, also known as the Indochinese Peninsula or Indochina, is the continental portion of Southeast Asia. It lies east of the Indian subcontinent and south of Mainland China and is bordered by the Indian Ocean to the west an ...

are waging against imperialism, because we share that common enemy in the United States."Grace Lee Boggs

Grace Lee Boggs (June 27, 1915 – October 5, 2015) was an American author, social activist, philosopher, and feminist. She is known for her years of political collaboration with C. L. R. James and Raya Dunayevskaya in the 1940s and 1950s. In th ...

and Yuri Kochiyama

was an American civil rights activist. Influenced by her Japanese-American family's experience in an American internment camp, her association with Malcolm X, and her Maoist beliefs, she advocated for many causes, including black separatism, t ...

. Both Boggs and Kochiyama were inspired by the civil rights movement of the 1960s and "a growing number of Asian Americans began to push forward a new era in radical Asian American politics."Chris Iijima

Chris Kwando Iijima (1948–2005) was an American folksinger, educator and legal scholar. He, Nobuko JoAnne Miyamoto, and Charlie Chin, were the members of the group ''Yellow Pearl''; their 1973 album, ''A Grain of Sand: Music for the Struggle by ...

, and William 'Charlie' Chin, performed across the nation as traveling troubadours who set the antiracist politics of the Asian American movement to music."

Clergy

The clergy, often a forgotten group during the opposition to the Vietnam War, played a large role as well. The clergy covered any of the religious leaders and members including individuals such as Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr. (born Michael King Jr.; January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968) was an American Baptist minister and activist, one of the most prominent leaders in the civil rights movement from 1955 until his assassination in 1968 ...

In his speech "Beyond Vietnam" King stated, "the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today: my own government. For the sake of those boys, for the sake of this government, for the sake of the hundreds of thousands trembling under our violence, I cannot be silent." King was not looking for racial equality through this speech, but tried to voice for an end to the war instead.

The involvement of the clergy did not stop at King though. The analysis entitled "Social Movement Participation: Clergy and the Anti-Vietnam War Movement" expands upon the anti-war movement by taking King, a single religious figurehead, and explaining the movement from the entire clergy's perspective. The clergy were often forgotten though throughout this opposition. The analysis refers to that fact by saying, "The research concerning clergy anti-war participation is even more barren than the literature on student activism."[Tygart, "Social Movement Participation: Clergy and the Anti-Vietnam War Movement"] There is a relationship and correlation between theology

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing the ...

and political opinions and during the Vietnam War, the same relationship occurred between feelings about the war and theology.

Draft evasion

The first draft lottery since World War II in the United States was held on December 1, 1969, and was met with large protests and a great deal of controversy; statistical analysis indicated that the methodology of the lotteries unintentionally disadvantaged men with late year birthdays. This issue was treated at length in a January 4, 1970 ''New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid d ...

'' article title

"Statisticians Charge Draft Lottery Was Not Random"

.

Various antiwar groups, such as Another Mother for Peace, WILPF, and WSP, had free draft counseling centers, where they gave young American men advice for legally and illegally evading the draft.

Over 30,000 people left the country and went to Canada, Sweden, and Mexico to avoid the draft.Beheiren

Beheiren (ベ平連, short for ベトナムに平和を!市民連合, ''Betonamu ni Heiwa o! Shimin Rengo'', "The Citizen's League for Peace in Vietnam") was a Japanese "New Left" activist group that existed from 1965 to 1974. As a loose coaliti ...

helped some American soldiers to desert and hide from the military in Japan.

To gain an exemption or deferment, many men attended college, though they had to remain in college until their 26th birthday to be certain of avoiding the draft. Some men were rejected by the military as 4-F unfit for service failing to meet physical, mental, or moral standards. Still others joined the National Guard

National Guard is the name used by a wide variety of current and historical uniformed organizations in different countries. The original National Guard was formed during the French Revolution around a cadre of defectors from the French Guards.

Nat ...

or entered the Peace Corps

The Peace Corps is an independent agency and program of the United States government that trains and deploys volunteers to provide international development assistance. It was established in March 1961 by an executive order of President John F. ...

as a way of avoiding Vietnam. All of these issues raised concerns about the fairness of who got selected for involuntary service, since it was often the poor or those without connections who were drafted. Ironically, in light of modern political issues, a certain exemption was a convincing claim of homosexuality

Homosexuality is romantic attraction, sexual attraction, or sexual behavior between members of the same sex or gender. As a sexual orientation, homosexuality is "an enduring pattern of emotional, romantic, and/or sexual attractions" to peop ...

, but very few men attempted this because of the stigma involved. Also, conviction for certain crimes earned an exclusion, the topic of the anti-war song "Alice's Restaurant

"Alice's Restaurant Massacree", commonly known as "Alice's Restaurant", is a satirical talking blues song by singer-songwriter Arlo Guthrie, released as the title track to his 1967 debut album ''Alice's Restaurant''. The song is a deadpan protest ...

" by Arlo Guthrie

Arlo Davy Guthrie (born July 10, 1947) is an American folk singer-songwriter. He is known for singing songs of protest against social injustice, and storytelling while performing songs, following the tradition of his father, Woody Guthrie. Gut ...

.

Even many of those who never received a deferment or exemption never served, simply because the pool of eligible men was so huge compared to the number required for service, that the draft boards never got around to drafting them when a new crop of men became available (until 1969) or because they had high lottery numbers (1970 and later).

Of those soldiers who served during the war, there was increasing opposition to the conflict amongst GIs, which resulted in fragging

Fragging is the deliberate or attempted killing by a soldier of a fellow soldier, usually a superior. U.S. military personnel coined the word during the Vietnam War, when such killings were most often attempted with a fragmentation grenade, some ...

and many other activities which hampered the US's ability to wage war effectively.

Most of those subjected to the draft were too young to vote or drink in most states, and the image of young people being forced to risk their lives in the military without the privileges of enfranchisement or the ability to drink alcohol legally also successfully pressured legislators to lower the voting age

A voting age is a minimum age established by law that a person must attain before they become eligible to vote in a public election. The most common voting age is 18 years; however, voting ages as low as 16 and as high as 25 currently exist

(s ...

nationally and the drinking age

The legal drinking age is the minimum age at which a person can legally consume alcoholic beverages. The minimum age alcohol can be legally consumed can be different from the age when it can be purchased in some countries. These laws vary between ...

in many states.

Student opposition groups on many college and university campuses seized campus administration offices, and in several instances forced the expulsion of ROTC

The Reserve Officers' Training Corps (ROTC ( or )) is a group of college- and university-based officer-training programs for training commissioned officers of the United States Armed Forces.

Overview

While ROTC graduate officers serve in all ...

programs from the campus.

Some Americans who were not subject to the draft protested the conscription of their tax dollars for the war effort. War tax resistance, once mostly isolated to solitary anarchists like Henry David Thoreau

Henry David Thoreau (July 12, 1817May 6, 1862) was an American naturalist, essayist, poet, and philosopher. A leading Transcendentalism, transcendentalist, he is best known for his book ''Walden'', a reflection upon simple living in natural su ...

and religious pacifists

Pacifism is the opposition or resistance to war, militarism (including conscription and mandatory military service) or violence. Pacifists generally reject theories of Just War. The word ''pacifism'' was coined by the French peace campaigne ...

like the Quakers

Quakers are people who belong to a historically Protestant Christian set of denominations known formally as the Religious Society of Friends. Members of these movements ("theFriends") are generally united by a belief in each human's abil ...

, became a more mainstream protest tactic. As of 1972, an estimated 200,000–500,000 people were refusing to pay the excise taxes on their telephone bills, and another 20,000 were resisting part or all of their income tax

An income tax is a tax imposed on individuals or entities (taxpayers) in respect of the income or profits earned by them (commonly called taxable income). Income tax generally is computed as the product of a tax rate times the taxable income. Tax ...

bills. Among the tax resister

Tax resistance is the refusal to pay tax because of opposition to the government that is imposing the tax, or to government policy, or as opposition to taxation in itself. Tax resistance is a form of direct action and, if in violation of the tax ...

s were Joan Baez

Joan Chandos Baez (; born January 9, 1941) is an American singer, songwriter, musician, and activist. Her contemporary folk music often includes songs of protest and social justice. Baez has performed publicly for over 60 years, releasing more ...

and Noam Chomsky

Avram Noam Chomsky (born December 7, 1928) is an American public intellectual: a linguist, philosopher, cognitive scientist, historian, social critic, and political activist. Sometimes called "the father of modern linguistics", Chomsky is ...

.

Environmentalists

Momentum from the protest organizations and the war's impact on the environment became focal point of issues to an overwhelmingly main force for the growth of an environmental movement

The environmental movement (sometimes referred to as the ecology movement), also including conservation and green politics, is a diverse philosophical, social, and political movement for addressing environmental issues. Environmentalists a ...

in the United States. Many of the environment-oriented demonstrations were inspired by Rachel Carson

Rachel Louise Carson (May 27, 1907 – April 14, 1964) was an American marine biologist, writer, and conservationist whose influential book ''Silent Spring'' (1962) and other writings are credited with advancing the global environmental m ...

's 1962 book ''Silent Spring

''Silent Spring'' is an environmental science book by Rachel Carson. Published on September 27, 1962, the book documented the environmental harm caused by the indiscriminate use of pesticides. Carson accused the chemical industry of spreading d ...

'', which warned of the harmful effects of pesticide use on the earth. For demonstrators, Carson's warnings paralleled with the United States' use of chemicals in Vietnam such as Agent Orange

Agent Orange is a chemical herbicide and defoliant, one of the "tactical use" Rainbow Herbicides. It was used by the U.S. military as part of its herbicidal warfare program, Operation Ranch Hand, during the Vietnam War from 1961 to 1971. It ...

, a chemical compound which was used to clear forestry being used as cover, initially conducted by the United States Air Force

The United States Air Force (USAF) is the air service branch of the United States Armed Forces, and is one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. Originally created on 1 August 1907, as a part of the United States Army Signal ...

in Operation Ranch Hand

Operation Ranch Hand was a U.S. military operation during the Vietnam War, lasting from 1962 until 1971. Largely inspired by the British use of 2,4,5-T and 2,4-D ( Agent Orange) during the Malayan Emergency in the 1950s, it was part of the ov ...

in 1962.

Musicians

Protest to American participation in the Vietnam War was a movement that many popular musicians shared in, which was a stark contrast to the pro-war compositions of artists during World War II. These musicians included

Protest to American participation in the Vietnam War was a movement that many popular musicians shared in, which was a stark contrast to the pro-war compositions of artists during World War II. These musicians included Joni Mitchell

Roberta Joan "Joni" Mitchell ( Anderson; born November 7, 1943) is a Canadian-American musician, producer, and painter. Among the most influential singer-songwriters to emerge from the 1960s folk music circuit, Mitchell became known for her sta ...

, Joan Baez

Joan Chandos Baez (; born January 9, 1941) is an American singer, songwriter, musician, and activist. Her contemporary folk music often includes songs of protest and social justice. Baez has performed publicly for over 60 years, releasing more ...

, Phil Ochs

Philip David Ochs (; December 19, 1940 – April 9, 1976) was an American songwriter and protest singer (or, as he preferred, a topical singer). Ochs was known for his sharp wit, sardonic humor, political activism, often alliterative lyrics, and ...

, Lou Harrison

Lou Silver Harrison (May 14, 1917 – February 2, 2003) was an American composer, music critic, music theorist, painter, and creator of unique musical instruments. Harrison initially wrote in a dissonant, ultramodernist style similar to his form ...

, Gail Kubik

Gail Thompson Kubik (September 5, 1914, South Coffeyville, Oklahoma – July 20, 1984, Covina, California) was an American composer, music director, violinist, and teacher.

Early life, education, and career

Kubik was born to Henry and Evelyn O. K ...

, William Mayer, Elie Siegmeister

Elie Siegmeister (also published under pseudonym L. E. Swift; January 15, 1909 in New York City – March 10, 1991 in Manhasset, New York) was an American composer, educator and author.

Early life and education

Elie Siegmeister was born January 15 ...

, Robert Fink, David Noon

David Noon (born 23 July 1946) is a contemporary classical composer and educator. He has written over 200 works from opera to chamber music. Noon's composition teachers have included Karl Kohn, Darius Milhaud, Charles Jones, Yehudi Wyner, Ma ...

, Richard Wernick

Richard Wernick (born January 16, 1934, in Boston, Massachusetts) is an American composer. He is best known for his chamber and vocal works. His composition ''Visions of Terror and Wonder'' won the 1977 Pulitzer Prize for Music.

Career

Wernick b ...

, and John W. Downey. However, of over 5,000 Vietnam War-related songs identified to date, many took a patriotic, pro-government, or pro-soldier perspective. The two most notable genres involved in this protest were Rock and Roll and Folk music. While composers created pieces affronting the war, they were not limited to their music. Often protesters were being arrested and participating in peace marches and popular musicians were among their ranks. This concept of intimate involvement reached new heights in May 1968 when the "Composers and Musicians for Peace" concert was staged in New York. As the war continued, and with the new media coverage, the movement snowballed and popular music reflected this. As early as the summer of 1965, music-based protest against the American involvement in Southeast Asia began with works like P. F. Sloan's folk rock

Folk rock is a hybrid music genre that combines the elements of folk and rock music, which arose in the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom in the mid-1960s. In the U.S., folk rock emerged from the folk music revival. Performers suc ...

song ''Eve of Destruction'', recorded by Barry McGuire

Barry McGuire (born October 15, 1935) is an American singer-songwriter primarily known for his 1965 hit " Eve of Destruction". Later he would pioneer as a singer and songwriter of Contemporary Christian music.

Early life

McGuire was born in O ...

as one of the earliest musical protests against the Vietnam War.

A key figure on the rock

Rock most often refers to:

* Rock (geology), a naturally occurring solid aggregate of minerals or mineraloids

* Rock music, a genre of popular music

Rock or Rocks may also refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* Rock, Caerphilly, a location in Wales ...

end of the antiwar spectrum was Jimi Hendrix

James Marshall "Jimi" Hendrix (born Johnny Allen Hendrix; November 27, 1942September 18, 1970) was an American guitarist, singer and songwriter. Although his mainstream career spanned only four years, he is widely regarded as one of the most ...

(1942–1970). Hendrix had a huge following among the youth culture exploring itself through drugs and experiencing itself through rock music. He was not an official protester of the war; one of Hendrix's biographers contends that Hendrix, being a former soldier, sympathized with the anticommunist view. He did, however, protest the violence that took place in the Vietnam War. With the song "Machine Gun

A machine gun is a fully automatic, rifled autoloading firearm designed for sustained direct fire with rifle cartridges. Other automatic firearms such as automatic shotguns and automatic rifles (including assault rifles and battle rifles) a ...

", dedicated to those fighting in Vietnam, this protest of violence is manifest. David Henderson, author of Scuse Me While I Kiss the Sky'', describes the song as "scary funk ... his sound over the drone shifts from a woman's scream, to a siren, to a fighter plane diving, all amid Buddy Miles

George Allen "Buddy" Miles Jr. (September 5, 1947February 26, 2008) was an American composer, drummer, guitarist, vocalist and producer. He was a founding member of the Electric Flag (1967), a member of Jimi Hendrix's Band of Gypsys (1969–197 ...

' Gatling-gun snare shots. ... he says 'evil man make me kill you ... make you kill me although we're only families apart.'" This song was often accompanied with pleas from Hendrix to bring the soldiers back home and cease the bloodshed. While Hendrix's views may not have been analogous to the protesters, his songs became anthems to the antiwar movement. Songs such as "Star Spangled Banner" showed individuals that "you can love your country, but hate the government." Hendrix's anti-violence efforts are summed up in his words: "when the power of love overcomes the love of power ... the world will know peace." Thus, Hendrix's personal views did not coincide perfectly with those of the antiwar protesters; however, his anti-violence outlook was a driving force during the years of the Vietnam War even after his death (1970).

The song known to many as the anthem of the protest movement was The "Fish" Cheer/I-Feel-Like-I'm-Fixin'-to-Die Rag

"I-Feel-Like-I'm-Fixin'-to-Die Rag" is a song by the American psychedelic rock band Country Joe and the Fish, written by Country Joe McDonald, and first released as the opening track on the extended play ''Rag Baby Talking Issue No. 1'', in Oct ...

first released on an EP in the October 1965 issue of ''Rag Baby''by Country Joe and the Fish, one of the most successful protest bands. Although this song was not on music charts probably because it was too radical, it was performed at many public events including the famous Woodstock

Woodstock Music and Art Fair, commonly referred to as Woodstock, was a music festival held during August 15–18, 1969, on Max Yasgur's dairy farm in Bethel, New York, United States, southwest of the town of Woodstock, New York, Woodstock. ...

music festival (1969). "Feel-Like-I'm-Fixin'-To-Die Rag" was a song that used sarcasm to communicate the problems with not only the war but also the public's naïve attitudes towards it. It was said that "the happy beat and insouciance of the vocalist are in odd juxtaposition to the lyrics that reinforce the sad fact that the American public was being forced into realizing that Vietnam was no longer a remote place on the other side of the world, and the damage it was doing to the country could no longer be considered collateral, involving someone else."

Along with singer-songwriter Phil Ochs

Philip David Ochs (; December 19, 1940 – April 9, 1976) was an American songwriter and protest singer (or, as he preferred, a topical singer). Ochs was known for his sharp wit, sardonic humor, political activism, often alliterative lyrics, and ...

, who attended and organized anti-war events and wrote such songs as "I Ain't Marching Anymore" and "The War Is Over", another key historical figure of the antiwar movement was Bob Dylan

Bob Dylan (legally Robert Dylan, born Robert Allen Zimmerman, May 24, 1941) is an American singer-songwriter. Often regarded as one of the greatest songwriters of all time, Dylan has been a major figure in popular culture during a career sp ...

. Folk and Rock were critical aspects of counterculture

A counterculture is a culture whose values and norms of behavior differ substantially from those of mainstream society, sometimes diametrically opposed to mainstream cultural mores.Eric Donald Hirsch. ''The Dictionary of Cultural Literacy''. Hou ...